Category: creativity

Story: draw from the well of what you know

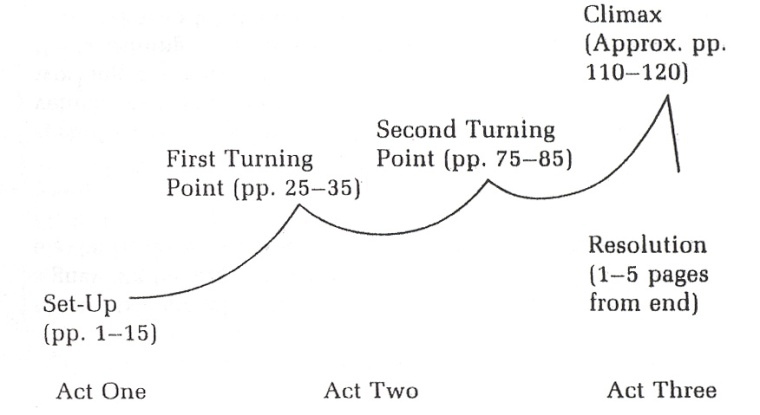

The Three-Act Story Structure

Once again I am diving into the struggle to write screenplays. In the past I got all snobby and looked down on the typical Hollywood story structure. I saw it as too conventional and I wanted to be artsy. Well, that got me a long ways.

In the mean time I have learned a thing or two, and have come to understand the conventions that drive Hollywood storytelling are, in fact, ancient paradigms that fit with human nature. In other words, the basic three-act structure (and it variations) was built into the human design by God. Sure, many have exploited it, have misused it, have done bad things with it – including making just plain schlock – but that does not nullify the fundamental character of the structure and how it engages with our minds.

With that I am trying to teach myself the structure, and how to use it to my advantage. Here are some examples:

I know that none of us work in a vacuum. We do not create ex nihilo. We work with what is given, and it is in our manipulations of forms that we discover new nuances. Structure is one of the great givens. I have decoded to use the three-act paradigm as strictly as I can and see what happens.

A couple vids on the topic:

>Why work doesn’t happen at work

>Interesting talk on the nature of disruptions and how the typical work environment, which is “designed” for productivty, may actually hinder getting things done.

http://video.ted.com/assets/player/swf/EmbedPlayer.swf

>Chess and "undirected" thinking

>

Si les insomnies d’un musicien lui font créer de belles oeuvres, ce sont de belles insomnies.

~ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Vladimir Kramnik

Chess World Champ 2000-2007

I’ve been wondering about creativity lately.

In 1926 Graham Wallas proposed a model to describe the process of creativity. This model followed four steps: 1) Preparation, 2) Incubation, 3) Illumination, and 4) Verification. There are two reasons why this model is historically important. First is the implication that creativity can be structured to some degree, and thus directed towards particular ends. The second is the recognition that creativity works both consciously and subconsciously, or a mix of directed and undirected thinking.

For many, the idea that creativity can be structured or controlled to some degree is of great significance. Think of the need in business to be innovative in order to remain competitive. Much has been written in this area and it is fascinating stuff. The mystery, though, is the subconscious aspect of creativity.

When we think about the game of chess we might assume that a pure Spock-like logical mind would be the best. Chess is a game of carefully calculated moves designed to find advantages against an opponent until a win is secured. But a pure emotionless rationality doesn’t work in chess. Sure, Deep Blue, the super computer that was able to beat the world’s greatest chess champion, Gary Kasparov, had no emotion, but it could also calculate around 2 million possible moves per second. Kasparov, on the other hand, can only calculate around 5 moves per second. (Even then, Kasparov still won one game and drew three out of six against Deep Blue). The human brain has limitations when it comes to the heavy lifting kinds of work that computers can do. Therefore, us humans need (and have) a different process for calculating chess moves. The answer, surprisingly, is the role our emotions and subconscious play in the decision making process.

Our subconscious is an interesting animal when it comes to creativity. When we tackle a problem our conscious mind is actively engaged, even working overtime. But so is our subconscious. When we get stuck and can’t find a solution we may disengage our conscious mind and move on to something else, but our subconscious mind can still be working on the problem. That’s why solutions often hit us when we are far from problem solving mode – like when we are just about to fall asleep at the end of a long day. Moments like these are examples of undirected thinking. Often it is best to get away from problem solving mode and do mundane activities like checking email or going for a walk, in order to let one’s subconscious to percolate on the problem.

There is an interesting story of undirected thinking in a recent chess tournament. Every year a number of the world’s top chess players gather in the Dutch seaside town of Wijk aan Zee for the Corus Chess tournament. In 2010 the reigning U.S. champion, Hikaru Nakamura, was tearing up the tournament, and not without a little smugness. Former world chess champion Vladimir Kramnik was to play Nakmura next. The night before Kramnik was pondering his strategy. He suspected the kind of chess opening Nakmura would choose, but he was struggling to find a way to neutralize that choice. He worked on it all afternoon and finally had to take a break. Later, in a classic moment of undirected thinking, the solution hit him:

“Around 3 o’clock last night I was pretty annoyed. I hadn’t found anything yet and it’s not possible you can equalize with the Dutch. Finally I had a shower, where I realized that I just shouldn’t take on e4!”

Saying he shouldn’t take on e4 is a way of describing in chess language that the solution against Nakamura is to not fall into the trap set by Nakamura’s opening strategy. In other words, even though he needed to take a break from actively thinking about his upcoming game, Kramnik’s subconscious continued on towards a solution which then came to him in the shower. The next day Nakamura played the opening Kramnik was expecting and Kramnik was able to handily neutralize the opening and play on to a win.

We have all had moments like that where, when we least expect it, a solution pops into our head as though out of nowhere. The fact is, it was there, just not in our conscious mind, but in our subconscious. The story above goes to show as well that even in the profound mental struggles of world class chess the human mind works as it does for all of us, as a mix of conscious and subconscious activities that can lead to both logically calculated thoughts as well as flashes of intuition. It is all part of how our rationality works, and the more we understand its complexities the better we might be able to exploit both directed and undirected thinking in a holistic creative process.

If you are interested in hearing Vladimir Kramnik talk about his win against Hikaru Nakamura, you can view his post-game press conference below. Note: If the credits at the beginning say “Round 1 Jan Smeets…”, that’s a mistake. This is all Kramnik.

>One week of an IDEO project

>The famous design firm IDEO is often considered the most creative such company in the U.S. I have heard about them for years, but now I am more interested because I have been doing some research on innovation and creativity. There design processes tends toward what they call controlled chaos. It is active, cooperative, democratic (mostly), and sometimes intense.

Recently they set up a camera to capture an entire week of work in two minutes:

Ten years ago ABC’s Nightline ran a story about IDEO and its design philosophy. Nightline asked IDEO to redesign the ubiquitous shopping cart in five days. This video is one of the best distillations of how to get a group to think & act creatively under time pressure and with a specific goal in mind.

>…they’ll be dancin’ in the streets (and elsewhere)

>Did you ever have a goofy idea that turned into something really grand? One reason I love the Internet is how it gets people jazzed about producing and posting things that would otherwise have been just another “wouldn’t it be cool” idea discussed over beers.

Example: This guy made this video:

If you want to watch it in Hi-Res, go here and choose the “watch in high quality” link under the video.

I should add this was sent to me by my friend Brian. Thanks Brian!

>"Hello, I’m Amy Walker. I’m twenty five…"

>I remember some college friends of mine studying the theater arts back in the day. Along with being amazed at their ability to memorize lines and produce wonderful performances, I also enjoyed their audition tapes (I believe this that’s what they were called). These friends of mine would put together audio tapes of themselves doing a variety of voices and dialects in order to demonstrate their range and talent. Often the tapes were very funny and quite good.

Of course today the audio cassette tape has gone the way of the pet rock. Now it’s all video, YouTube, etc. That’s what I assume this is:

I have to say I think that’s a lot of fun, and excellent.