>The title of this post is also the title of my thesis which I wrote for my Masters of Business Administration program, which I just completed. To get some idea of what sparked my thinking and led to my thesis topic you can watch the video clip below about workers in developing countries as they support the demands of the developed world. You have already heard about sweat shops in third world countries. Here is what they look like:

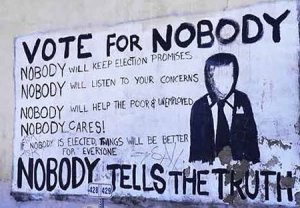

…or this parody from The Onion brings up the issue in its way:

http://www.theonion.com/content/themes/common/assets/videoplayer/flvplayer.swf

What are we, those of us in the most powerful nations on earth, going to do about the globalization of capital and corporate power? The world may be becoming increasingly, economically “flat”, as Tom Friedman says, but is it becoming morally flat as well?

It may sound strange to ask what we are “going to do” about globalization. Isn’t it a good thing? Isn’t it about the expansion of wealth and freedom? Isn’t it about the Internet and better communication? What we don’t typically hear about is the hidden costs of globalization, or about what that word conjures up in the minds of those in the developing world. For much of the world globalization includes the realities in the video above. For the rest of us that reality is often hidden.

I am, by nature, a rather conservative type. I don’t get easily bent out of shape over issues. I don’t seek revolution at the drop of a hat. I also grew up a Christian and was, until a few years ago, a registered Republican. I am still a Christian, and because of taking my faith seriously I could no longer be a Republican. Now I am an independent. But it’s not really about politics. It’s about a perspective on the world, on how I want to live. It’s about what kind of person I want to be and where I want to end up. And it’s also about the kind of world I want for my children and their children.

When it came time for me to choose a topic for my MBA thesis I felt the need to tackle something to do with ethics. I felt I needed to address, for myself, the underlying moral issues inherent in business and economics before I went out from my schooling into more business adventures. So I picked the topic of the treatment of women workers in global supply chains and the ethical implications for businesses that rely on the benefits from those supply chains (like lower costs and faster delivery, etc.). My thesis became, for me, a kind of introduction to the larger topic of ethics and, more specifically, how should someone who claims to be a Christian act in the world.

The following is from Chapter One of my thesis:

Consider this scenario: when a shopkeeper opens her doors in the morning and hangs out the welcome sign it is time to get to work. The pressures of the day quickly crowd in as she must meet the demands of her customers and her business’ bottom line. She must manage her time and her employees, deal with suppliers, and try to make plans for the future while also trying to fully understand the past. Questions of ethics are considered, if considered at all, largely in the immediate context of the day-to-day routine. Our shopkeeper will have to decide where she stands on being truthful and honest with those whom she works; she will make ethical decisions around how she manages her accounting and pays her vendors; she may even face moral questions about what products she sells and whether they are good for her community.

Now let’s assume this shopkeeper is also a Christian, one who makes claims to be a follower of Jesus Christ, and one who participates in the life of Christian culture. The ethical issues for the shopkeeper will not be any different from any other shopkeeper. However, she now carries the burden of having to follow some explicit commands with regard to the world, most notably to love her neighbor as herself. And who is her neighbor? Is her neighbor only the immediate customer or vendor with whom she does business? Or, given that she lives in an increasingly globalized world, does her neighbor include those with whom she now has connections, even though they may be on the other side of the planet and at the distant end of her supply chains?

If our shop keeper then decides that she does want to build her business around the idea of loving her neighbor as herself, and then apply that philosophy to her dealings with her supply chains, she must decided how to do that. What options are available to her? Does she choose servant-leadership as a leadership style? That is, will she seek to be a servant first and, as Greenleaf (1991) says, “to make sure that other people’s highest priority meeds are being served” (p. 7)? Does she choose to buy only from suppliers that treat their employees well? Does she seek to instill corporate social responsibility into her business practices?

These kinds of questions might be of little importance if it were not for two realities. The first is that the world is more connected than ever before. The second is that many workers in global supply chains, particularly those in developing countries, often have few of the rights or freedoms those in Western and Northern societies take for granted and may even assume to be inalienable. This is not to say that the benefits of free-market capitalism have not brought greater wealth to many developing countries, nor that many of the world’s poor have not seen at least some economic improvement to their way of life. However, as the gap between the world’s poor and the world’s rich gets bigger, and as facts continue to come out regarding the all too often harsh treatment of laborers, including women and children, within global supply chains, one cannot help but ask whether a laissez fair, free-market philosophy is the best approach for creating a fair and just system that benefits all stakeholders appropriately.

A Christian business person must ask these kinds of questions, not merely because economic systems come with their own set of moral presuppositions about human nature and human needs, but also because in the day-to-day world of business, as it is in life, one’s actions flow from one’s beliefs. If a Christian is to take seriously the commandment to love her neighbor as herself, then it only makes sense that that command, that challenge, would raise such questions. Maybe one of the great historical ironies is the interconnectedness of free market capitalist thinking and Christian theology; ironic because one system is based on self-centeredness for its success and the other is based on other-centeredness. Our shopkeeper will have to decide if this interconnectedness is both useful and valid.

I go on to describe how global supply chains work, including the fundamental pressures they impose, such as cheaper labor and fast delivery. I then describe how those pressures necessarily create negative conditions for many workers. I then describe the common conditions of working women in those supply chains. (I chose women workers because of the data available and because they represent more than half of the global workforce while often being in the weakest position with regards to labor rights and fair treatment.) Finally I examine how some have sought solutions, for example the concepts of corporate social responsibility (CSR), fair trade, and servant leadership.

I also examine how Christianity has shifted away from social concerns by becoming a personal/private faith thing rather than an “all of life” thing. This shift has led many Christians for forsake the requirements of their faith, that is, to be “salt of the earth” as it where. Too many Christians, I argue, see their faith as a purely private matter, except for a small handful of political issues.

I do not see globalization as a specifically “Christian issue.” There are many perspectives and answers available. But I find narrowing the scope down a bit helps to crystallize the issue for me. I do not see in the Bible anything specifically about free trade, but I do see a lot about feeding the hungry and helping the poor. Recently a professor of mine related a story where he was teaching about globalization and one of his students, a man from Africa, said that when he hears the word “globalization” he knows it to mean Western imperialism. There is something that rings true for me about that student’s perspective, and that bothers me.

Much of my thinking has shifted over the past several years as I have tried to take seriously the teachings of Jesus. The irony is that the teachings of Jesus contradict much of modern, popular Christianity in both its focus and its call to action. I have become convinced that mainstream, right-wing (and many left-wing) Christians just may have become the new Pharisees – the pious religious types who Jesus railed against and who eventually killed him. They do church really well, but their hearts have become hard – and I know what I’m talking about because I am one of them. Because of this I chose to focus on the implications of the commandment to love one’s neighbor as a foundational challenge. I figured that commandment cuts through a lot of garbage.

This video interview with Tony Campolo offers some idea of what I am talking about:

I won’t say that I am in Campolo’s camp entirely, and I don’t cite him in my thesis. However, I will say that his teaching challenges me deeply.

I am also challenged by numerous other thinkers, most of whom are not Christians, and some are even anti-Christian. But I believe truth can be found just about everywhere. The following video clips further pad out the topic.

Christian “progressive” Jim Wallis talks about living out one’s faith:

Left-left-wing academic and leading progressive thinker Michael Parenti on globalization and what it really means:

Parenti is no fan of Christianity by any means, or any religion really, but he is a very sharp thinker and erudite historian.

Brilliant and exacerbating Noam Chomsky on globalization:

I find myself more and more fascinated with Chomsky’s work. Years ago I read a book of his on linguistics for my MA thesis. Since then I have most only heard him speak. His observations on power politics are illuminating. Chomsky and Parenti do not see eye-to-eye on several issues.

Naomi Klein, author of The Shock Doctrine speaks on the topic of global brands, the topic of her famous book No Logo:

http://video.google.com/googleplayer.swf?docid=2343596870021245516&hl=en

Famous activist, historian, and progressive thinker Howard Zinn on American Empire (a topic related to globalization):

Not all is doom and gloom. Consider the Tony Campolo and Jim Wallis clips above and the clip below.

Towards a solution – Fair Trade:

I have to say the process of writing and defending my thesis was longer than I anticipated, but it has bee a very rewarding process. I am glad I finished school and I am excited about my future career. I will say, however, that I have not, for me personally, solved the issues raised in my thesis. I still struggle to fulfill the commandment to love my neighbor, and I’m sure I always will.

References

Greenleaf, R. K. (1991). The servant as leader. Westfield, IN: The Robert K. Greenleaf Center.